Sometimes, especially in the prepper/survivalist equipment world, one can tell upon cursory visual inspection or review of specifications that an item or piece of gear has value; but until you actually put the piece to work with your own bare hands, the level of utility and the piece’s place in the universe is often difficult to quantify. This is exactly where I found myself at the precise moment I opened the white box with the orange circle and “HENRY” logo emblazoned on its cardboard face. My FFL dealer looked at the mysterious contents of the box, narrowed his eyes, cocked an eyebrow, and queried, “Why’d you get that?” I wasn’t exactly sure myself at that intersection of space/time coordinates, but I was certainly going to find out. Our subject? An arm that’s an enigma wrapped in a mystery to most who see it: a .410 shotgun made by Henry Repeating Arms…that’s a lever action.

orange circle and “HENRY” logo emblazoned on its cardboard face. My FFL dealer looked at the mysterious contents of the box, narrowed his eyes, cocked an eyebrow, and queried, “Why’d you get that?” I wasn’t exactly sure myself at that intersection of space/time coordinates, but I was certainly going to find out. Our subject? An arm that’s an enigma wrapped in a mystery to most who see it: a .410 shotgun made by Henry Repeating Arms…that’s a lever action.

By Drew, a contributing author of Survival Cache & SHTFBlog

What’s In The Box??

Yes, the Henry Repeating Arms model H0-18-410 is indeed a lever-action shotgun. Though the idea is not new – not even by a long stretch (Winchester’s John Browning-designed model 1887 has been knocking ducks out of the sky and arming Terminators since the late 19th century), Henry’s interpretation and execution of the concept is but a new take on the theory.

Built on Henry’s .45-70 lever-action frame, the .410 is an old friend as soon as it jumps into your hands and you cycle the action. Though possibly seeming obsolete to the uninitiated and unappreciating unwashed masses, Henry’s team has paired a satin-finished, nicely fitted and checkered American walnut stock fore and aft with a matte blued finish on the steel – a combination guaranteed to make levergun lovers such as myself go a little weak in the knees. Henry offers two versions of their .410 shotgun – a 24-inch barreled model with a big ol’ brass bead for sighting reference and screw-in chokes, and a 20-inch barreled system with adjustable rifle-type buckhorn sights, a drilled and tapped receiver, and a fixed cylinder bore choke – no screw-in chokes. My shotgun is the former configuration – I chose the extra versatility of the screw-in chokes (a single, full choke is provided, though other chokes are available at about the $20 mark) over the more precise sighting possibilities of the rifle sights – it’s a shotgun, not a rifle, right? More on this later.

Image from henryusa.com

Rounding out the package is a nice squishy black recoil pad on the walnut buttstock (to soak up the negligible recoil of the mighty .410), and a welcome addition that many shotgun manufacturers seem to neglect: integrated sling swivels for a standard hunting-type sling. There is no compatibility from the factory with tactical-type single-point or two-point slings – and that’s fine by me; this shotgun’s comfort zone doesn’t include room clearing. The only accessories I added to this Henry .410 was a Butler Creek Ultra Padded nylon sling with cartridge loops so I could have an extra six shotgun shells ready to rumble.

Also Read: AR-7 Survival Rifle Review

I did want to make special mention of the trigger on this Henry; though most mass-produced shotguns have a trigger that breaks like a green maple branch, my subject .410 had a trigger that belongs on a moderately-priced precision rifle; I’ve never had any lever-action rifle – let alone a shotgun – with a trigger break as clean and crisp as this particular Henry offers. Outstanding quality from the fine people in Bayonne, NJ! Also of note is the Henry’s proud proclamation: Made in America or not made at all!”

Going Down The Tubes

What sets Henry leverguns apart from other manufacturers such as Marlin (whose lines the Henry seems to borrow from) and Winchester is the loading and feeding system. All three of these manufacturers sport tubular, in-line cartridge magazines that live underneath the barrel. However, while Winchester and Marlin load through a spring-steel gate on the side of the receiver, Henry chose to buck the convention and utilize a tried-and-true, proven magazine system that incorporates a removable brass feed tube (a la pretty much every tubular magazine .22 LR rifle EVER) to house the spring and cartridge follower. A short twist on the knurled end cap and the brass tube slides out with well-oiled, smooth precision, allowing the shooter to load five 2 ½” long .410 shells into the magazine. Push the brass feed tube back down into the magazine, twist to lock, work the lever, and you’re in business. The simplicity of the feed tube system is appreciated, though often maligned by those who have used other manufacturer’s traditional loading gate systems.

Also Read: Survival Gear Review: Benjamin Trail NP2 Pellet Rifle

Though for brass-cased cartridges, I’ll admit I generally prefer a loading gate system (mostly due to familiarity), the feed tube has some definite benefits to our survivalist-bent target audience. First and foremost, you can load the Henry with one hand. Lock the Henry between your knees or in another secure area, and one hand can easily retract the feed tube, drop in the desired payload, and replace the tube; rifles with  loading gates universally require one firm hand on the gun to hold it from pushing away, and the other hand to wrestle cartridges into the magazine. Secondly, you can load the Henry quite easily with gloves on; a traditional loading gate system will, in my experience, chow down on your glove with reckless abandon as soon as you need to push that cartridge in past the loading gate. Third, you don’t need lumberjack hand strength to load the gun – trained children, the old, the weak, the tired – all can feed and use the Henry with aplomb and ease. Fourth, it’s simple and safe to unload: pull out the magazine feed tube and dump the roads on the ground or convenient surface, then lever the round out of the chamber; your gun is clear. Traditional loading gate systems require you to lever every single round through the gun to unload – a system that’s rough on ammo and very safety-intensive; if you’re tired, cold, or otherwise distracted, the possibility of a negligent discharge increases dramatically.

loading gates universally require one firm hand on the gun to hold it from pushing away, and the other hand to wrestle cartridges into the magazine. Secondly, you can load the Henry quite easily with gloves on; a traditional loading gate system will, in my experience, chow down on your glove with reckless abandon as soon as you need to push that cartridge in past the loading gate. Third, you don’t need lumberjack hand strength to load the gun – trained children, the old, the weak, the tired – all can feed and use the Henry with aplomb and ease. Fourth, it’s simple and safe to unload: pull out the magazine feed tube and dump the roads on the ground or convenient surface, then lever the round out of the chamber; your gun is clear. Traditional loading gate systems require you to lever every single round through the gun to unload – a system that’s rough on ammo and very safety-intensive; if you’re tired, cold, or otherwise distracted, the possibility of a negligent discharge increases dramatically.

Another side benefit of the tube feed system that is shotgun-shell specific: I’ve tried Winchester .410 shotguns based on the 94 rifle pattern, and loading plastic shells through a feed gate pretty much guarantees plastic shavings in the gun; the shotgun shell hull can get peeled as it pushes past the receiver, cartridge stops, and feed gate, ensuring a rainbow-colored smorgasbord will be decorating your shotgun’s innards. A tube feed system negates this issue entirely.

The brass feed tube, though, is the Achilles’ heel of the Henry’s “repeater” title: you’d best take good care of the brass tube magazine parts – if they are neglected, lost, bent or damaged, you have reduced your repeating shotgun to a really nice single shot lever action. The brass feed tube is the shotgun’s (and, as an extension, possibly YOUR) life support: while the tube is sturdy and well-made, it’s an essential requirement to treat it well. Nurture its very well being and keep an eye on it to ensure your Henry is functioning to its maximum capability when you need it to nurture your very well being.

But…Why a .410 Lever Action?

And here we are: figuring out why we’re even considering the Henry .410 Lever Action SHotgun for our survival uses…and possibly, why it even exists in the first place. The crux of the issue is twofold: the .410 isn’t exactly a powerhouse, and the lever action is a tad unorthodox for a shotgun. Let’s address these issues separately, then discuss how this Henry rises to the task despite the rather unorthodox approach.

Related: The Katrina Rifle

The .410 shotgun (the .410 is not a gauge, but technically a bore size/caliber.) has long been cursed for its supposed lack of punch. Aficionados and “specialists” (snobs?) deem the .410 to be the ultimate expression of technique and skill – if you can kill it/hit it with a .410 when everyone else needs a 12 gauge to accomplish the same mission, then clearly you must have no shotgunning peer in the immediate area. The plain and simple fact is that – all other things like shot size and barrel length being equal – the shot in a .410 is moving almost as fast as the shot from a 12 or 20 gauge…so the .410 has the same theoretical power as a bigger gauge of shotgun, just less volume. Case in point: a box of 2 ½” .410 shells – Remington Express Long Range manufacture in no. 7 ½ lead shot – boasts 1,250 feet per second (FPS) velocity on its box. For comparison’s sake, Remington Express Long Range 12 gauge, 2 ¾” shells with 7 ½ load shot are advertised at 1,330 fps. That’s 80 fps advertised velocity difference on a pellet that is truly minuscule: a number 7 ½ shot pellet is .095” in diameter and just 1.46 grains – so we’re talking not even a foot-pound of energy per pellet difference between a 12 gauge and a .410 with this one example of shot size and manufacturer. Your mileage may vary, but I’ll bet not by much.

as fast as the shot from a 12 or 20 gauge…so the .410 has the same theoretical power as a bigger gauge of shotgun, just less volume. Case in point: a box of 2 ½” .410 shells – Remington Express Long Range manufacture in no. 7 ½ lead shot – boasts 1,250 feet per second (FPS) velocity on its box. For comparison’s sake, Remington Express Long Range 12 gauge, 2 ¾” shells with 7 ½ load shot are advertised at 1,330 fps. That’s 80 fps advertised velocity difference on a pellet that is truly minuscule: a number 7 ½ shot pellet is .095” in diameter and just 1.46 grains – so we’re talking not even a foot-pound of energy per pellet difference between a 12 gauge and a .410 with this one example of shot size and manufacturer. Your mileage may vary, but I’ll bet not by much.

Where the bigger gauges shine is sheer density of shot – a 2 ½” .410 throws but ½ ounce of shot, or a quantity of about 170 pellets at number 7 ½ size – where a 2 ¾” 12 gauge kicks out 2.5 times as much 7 ½ sized shot at 1 ¼ ounces, or about 425 pellets. So just by comparing the number of little lead spheres coursing towards your chosen target at high velocity, it’s easy to mathematically devise that it’s just simply gonna be easier to hit a moving target with more pellets with the bigger 12 gauge than the .410 – so a .410 will require practice and a touch of skill to get a handle on hitting moving targets with any kind of authority. However, with solid hits in a vital area, I’ll lay wages that your small game target isn’t going to be able to tell if you shot it with a .410 or a 12 gauge.

“But what about slugs?” You may ask…and that’s a great question. A 1-ounce Foster-type lead slug from a 12 gauge has legendary impact power – I’ve personally seen deer flip hooves-over-head upon being the recipient of a solid 12 gauge slug hit in the brisket, and many authorities recommend a 12 gauge with slugs as a big bear deterrent in Alaska…so the 12 gauge with slugs is nothing to sneeze at. However, the .410 bore throwing slugs is a wholly different kettle of fish.

You Might Like: Walking Around Rifle

A Remington 2 ½” long .410 slug load shoots a ⅕ ounce slug – roughly 90 grains – at about 1,830 FPS velocity. This equates to roughly 650 ft-lbs of energy at the muzzle. However, that stubby little lightweight slug sheds velocity FAST – at 50 yards it’s moving at a shade over 1300 FPS and the bullet energy has been halved at less than 350 ft-lbs of energy. At 100 yards, that ⅕ ounce of cast lead is barely serving up 200 ft. lbs of energy. Folks, we’re looking at roughly the same performance as a .357 Magnum shooting a 125-grain bullet – from a handgun. Around the parts I hail from, we consider 1,000 ft-lbs of energy to be a good baseline for killing a whitetail deer – so though I’m sure they have felled many a deer, to be safe the .410 slug loads really need to be kept to coyote-sized game for clean kills.

little lightweight slug sheds velocity FAST – at 50 yards it’s moving at a shade over 1300 FPS and the bullet energy has been halved at less than 350 ft-lbs of energy. At 100 yards, that ⅕ ounce of cast lead is barely serving up 200 ft. lbs of energy. Folks, we’re looking at roughly the same performance as a .357 Magnum shooting a 125-grain bullet – from a handgun. Around the parts I hail from, we consider 1,000 ft-lbs of energy to be a good baseline for killing a whitetail deer – so though I’m sure they have felled many a deer, to be safe the .410 slug loads really need to be kept to coyote-sized game for clean kills.

No Really – Why a Lever Action?

Aye, there’s the rub. People can get the philosophy behind the .410 and generally agree it has merit within its envelope – but try to get them to understand why a lever-action SHOTGUN makes sense and you’ll start to lose your audience’s understanding. Why get a levergun when there are other time-proven designs in .410 like the Remington 870, or even a break-open H&R/New England Firearms Handi-Rifle?

Well, the lever-action shotgun has immediate appeal to me (and I’ll bet a lot of others) because I (we) grew up shooting leverguns. My first “real” deer rifle was a Winchester 94 “Trapper” in .44 Magnum. My first repeating rifle was a Marlin Model 39A. To this day, the gun I reach more most often when deer season opens up is a rare Marlin 336ER in .356 Winchester. To me, lever actions epitomize simplicity, speed, effectiveness, and fast-handling qualities – and this Henry is absolutely no different. I’ve been able to harvest multiple flushing ruffed grouse in thick cover with the Henry due to the Henry coming to the shoulder in a lively fashion and behaving like my beloved Marlin deer rifle. If you’ve used leverguns in the past, the Henry .410 lever action shotgun will certainly play nice for you.

Survival Debate: Henry A7 vs Springfield Armory M6

Another argument that can be mustered in defense of the Henry is reliability. Leverguns have long been lauded as reliable arms – they work as long as they’re not broken, and they usually will run well even when gummed up with many years worth of outdoors gunk caking their innards. Where Henry Repeating Arms built the HO18-410 shotgun on their .45-70 platform, the design was already optimized for flawlessly eating big stubby ammunition – so the .410 is a logical progression and functions with precision. I have had zero malfunctions with the Henry, whether cycling the blued steel lever as forcefully as I could, or at a leisurely rate. The design works, and works well – and a good man with a levergun can easily keep pace with a guy running a pump-action…or possibly stay nipping at the heels of a guy with a semi-automatic shotgun.

built the HO18-410 shotgun on their .45-70 platform, the design was already optimized for flawlessly eating big stubby ammunition – so the .410 is a logical progression and functions with precision. I have had zero malfunctions with the Henry, whether cycling the blued steel lever as forcefully as I could, or at a leisurely rate. The design works, and works well – and a good man with a levergun can easily keep pace with a guy running a pump-action…or possibly stay nipping at the heels of a guy with a semi-automatic shotgun.

A facet to consider that certainly doesn’t harm the reliability is that the Henry’s action is completely enclosed. With no loading gate at the side or bottom to expose the shotgun’s guts, the likelihood of debris entering the firearm’s innards is lowered substantially. I’ve frequently returned to the truck after a day of hunting close cover areas, only to find a fir branch or pine needles stuck in the gun’s action. A clean gun is a happy gun, and the longer you can keep foreign objects from collecting in the gun, the better the chances are the gun will work when you need it.

The last Henry debate point I’m bringing to the repeating shotgun table is safety. Lever action arms are oft reviled in the safety department due to the fact that (surprise, surprise!) the gun will probably go off if you’re a moron and keep your finger in the trigger guard while cycling the action during a brisk unloading session. As stated previously, the Henry negates this issue handily by allowing the user to dump all the rounds out of the tubular magazine, and then cycle the action once to extract any chambered shells. If this manual of arms is followed, there is zero chance the gun can go off while unloading – even if your finger somehow finds its way onto the trigger.

Related: Tru-Bore 12 Ga Chamber Adapter Review

Also, the exposed hammer allows a level of visual safety that just isn’t available on other repeating shotguns. A simple visual inspection can tell you if the gun is cocked and ready to fire – a wonderful benefit for teaching, and also for loaning the shotgun to people who may not be “gun guys/gals”; you can glance at the gun in their hands – even from a distance – and know instantaneously if the Henry is cocked and ready to fire. A round of applause to Henry for also resisting the urge to install an eyesore and annoyance of a cross-bolt safety in the receiver to please lawyers – the gun’s lines remain clean and unfettered, and the internal hammer safeties ensure the gun won’t go off unless the trigger is pulled.

a wonderful benefit for teaching, and also for loaning the shotgun to people who may not be “gun guys/gals”; you can glance at the gun in their hands – even from a distance – and know instantaneously if the Henry is cocked and ready to fire. A round of applause to Henry for also resisting the urge to install an eyesore and annoyance of a cross-bolt safety in the receiver to please lawyers – the gun’s lines remain clean and unfettered, and the internal hammer safeties ensure the gun won’t go off unless the trigger is pulled.

Running and Gunning

I certainly wasn’t going to have a gun like this Henry in my possession and just shoot it a couple times at clay pigeons and dig it out to show friends the “bet you’ve never seen one of these!” shotgun. No sir, I wanted to test the utility of the Henry .410 and find its place in the big scheme of prepper stuff. Field work was required.

Henry was kind enough to expedite sending the shotgun to me to make sure I could test the .410 on my yearly bird-hunting expedition in Northern Maine. Knowing ruffed grouse would be the primary game, I needed to settle on dialing in the ammunition for the task at hand, and also pattern the shotgun to check shot density. Knowing roughly how big a grouse was, I tried different shot sizes at different distances to see what appeared to be the best envelope that the Henry was most effective inside. Fortunately, the grouse is approximately the same size as other small game, so it was a great benchmark to compare how the shotgun would work against other, rather diminutive fur-bearing creatures.

Normally, when I hunt birds with 12 or 16 gauge shotguns, I gravitate towards #5 or #6 shot to wrangle a bit more distance and punch; the heavier shot provides a better chance at hitting game when coursing through light foliage. However, I found that even with the supplied full choke, #6 shot just wasn’t putting many pellets on the target area at my self-imposed 25 yards. So, I made the decision to bump down a shot size to #7 ½, and had much better shot pattern density with 10-12 pellets in the desired 8” target area at 25 yards. Pacing back to even just 30 yards, the shot pattern opened wide and I was lucky to get more than 4 or 5 pellets on the circle – so now I knew the shot size and range where the shotgun would be most effective for me. Chances were excellent that I would be shooting at moving birds, so that shot pattern would need to be effective and predictable, and the Remington Express loads delivered nicely.

Since the action length is limited to use of 2 ½” long shotgun shells only, I was curious about the effectiveness with its smaller shot payload – most other semi- and pump-action .410s offer 3” chambers, with a correspondingly heavier shot charge. While I didn’t have a 3” gun to test against and maybe get some on-paper results, I’m happy to say that in the real world, the 2 ½” chamber worked well – as long as I stayed in that 25-yard box.

Two examples for you to consider:

Case one: while hunting grouse with a buddy on our trip, he flushed a grouse from a juniper bush below me and the bird took off like a feathered Apache helicopter and made a beeline for the heavy cover to my left. I heard the bird break, caught the motion, and fluidly brought the shotgun to my shoulder in a well-rehearsed, almost subconscious motion. The bead found the bird rocketing past me through light scrub brush, swept past in a quick lead, and the bird fell a split second after the trigger broke cleanly beneath my finger.  The range was about 15 yards, and I was stunned I made the shot – I’d had it in my head that the little .410 just wouldn’t make the grade on wingshooting. I was delightfully wrong.

The range was about 15 yards, and I was stunned I made the shot – I’d had it in my head that the little .410 just wouldn’t make the grade on wingshooting. I was delightfully wrong.

Case Two: on the same trip, I had a grouse glide past my head and land on a stump, about 50 yards away. I readied the Henry for action on my shoulder and stalked slowly to about 35 yards. At this point, the bird was getting seriously cagey with my approaching presence, so I cocked the shotgun, took careful aim, and let fly, thinking that the still target would provide enough possibility to a few pellets to hit effectively. Pellets did hit – I’m not sure how many – but they lacked the authority or numbers for a clean kill, and the bird toppled, but hit the ground running hard through the dense brush. I gave chase for about 20 minutes, and thankfully the bird was harvested a few minutes later by my hunting partner. I made a mental note not to move out of the comfort zone of the shotgun again; wounding and not recovering game is one of the worst feelings ever.

I did buy a couple boxes of slugs for the Henry and tried them out off the bench at the 25-yard mark. I’m sure the full choke didn’t help things – the big brass bead sight sure didn’t – but the slugs formed a huge 10” pattern on the paper, with one of the slugs keyholing. If you’re planning on possibly shooting slugs more frequently from your .410 Henry, I would steer you towards the shorter rifle-sighted version which has no choke to contend with, as well as the capability of mounting optics; slugs were not a viable option in my gun except at very close range. In my eyes, the 24” barreled bead-sighted Henry like mine is far better suited to be a shot-delivering shotgun than a slug-delivering shotgun. But really, that was my plan all along anyway.

Little Bore Fish in a Big Gauge Pond

Reading reviews for the Henry online, I seem to see writers simply noting that the Henry is “a lot of fun!” while casting off the utility the levergun provides. Perhaps they didn’t like the compromise the littlest shotgun represents, or the fact that slugs didn’t play nice with this model and so it’s not truly a do-it-all wonder gun. However, limiting this shotgun to the “fun only” category is a serious mistake – and in doing so, many potential users likely miss out on a great opportunity to have a nicely effective gun for a lot of purposes.

Also Read: 30-30 Lever Guns

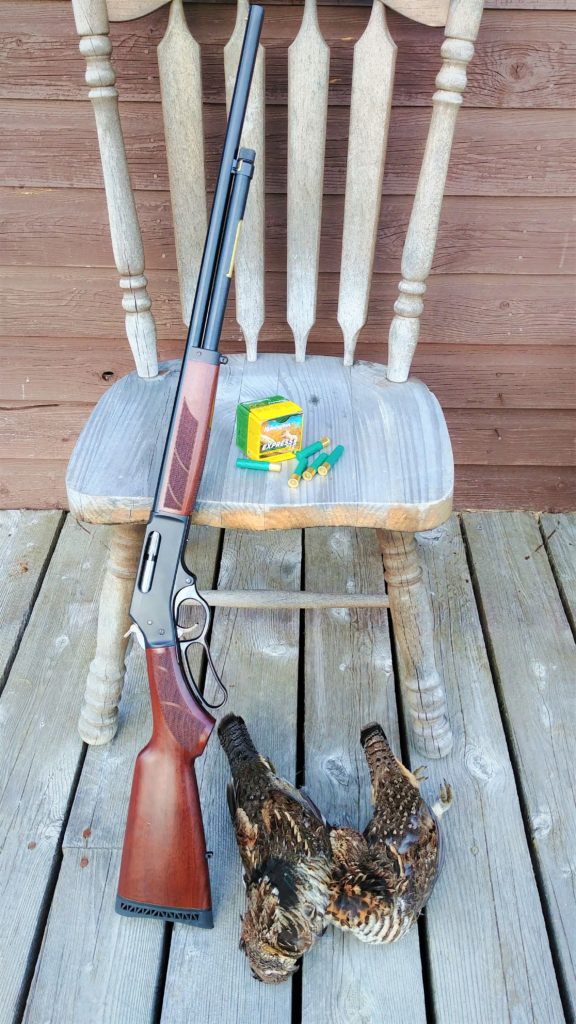

Obviously, this shotgun can be used for small-game hunting – I’ve proven that many times with the shotgun since it’s been in my possession. Ruffed grouse, gray and red squirrels, and nuisance chipmunks have all fallen to the the little Henry that could while in my hands. Rabbits and hares, woodchucks, beaver, porcupines, and other similarly-sized critters will all crumple convincingly to a well-placed pattern of pellets from this levergun. Its foraging and pest control potential is all out of proportion to the size of the hole in its muzzle, and when you consider the fact that you can fit roughly 2-3 times the amount of .410 ammunition in the same space as box of ammo for a 12 gauge, its place in the great survivalist universe starts becoming clear. Leave this beautifully made shotgun and a bunch of shells at the homestead, farm, or BOL, and be guaranteed to have an effective gun for feeding your family, eradicating unwelcome rodents in your garden, and even providing defense if need be at close range with slugs or buckshot rounds.

Though some may throw up the “but the .22 will do all that and more” rebuttal with quivering bottom lip and furrowed brow, the point of fact is that the shotgun is a much more effective arm at the .22-type tasks than the .22 actually is, inside range limitations, and providing ample ammunition supply. And if your survival or hunting plans includes people who simply aren’t practiced on precision firearms shooting, the shotgun will prove to be a better arm for supplying these types with a gun they can effectively collect game with. The slower loading speed and limited 5-shot capacity means that the supply of ammunition won’t be ripped through, and the .410’s small(er) ammunition size ensures that a heady supply can be kept in a short amount of space – so the apartment dwellers and tiny home denizens can raise their hands in supplication to the prepper shotgun Gods as well.

Long and short? The Henry H018-410 .410 Lever Action Shotgun is a beautifully built, high quality, very rugged shotgun that will serve many people well as long as they stay inside its working range – and as long as they wander past the unknown and give the lever action .410 a chance to prove its worth.

Visit Amazon Affiliate Sponsors of Survival Cache

The post Survival Gear Review: Henry .410 Lever Action Shotgun appeared first on Survival Cache.

from Survival Cache https://survivalcache.com/survival-gear-review-henry-410-lever-action-shotgun-best-survival-henry-arms/

No comments:

Post a Comment